Therefore, they are much easier to work with than five-minute or 10-minute increments, which would equate to 1/12 of an hour or 1/6 of an hour respectively. Three-minute as well as six-minute increments can be used to quickly calculate rates, such as distance and speed, as three minutes is exactly 1/20 of an hour and six is 1/10 of an hour. Here, his chronograph comes to the rescue! Indy knows that he can use a simple calculation to determine his fate, using the mighty ‘Rule of three’ and his trusted old timepiece with those funky hash marks. Imagine Indy being chased, trying to get away in his little beat-up bi-plane, having somehow to figure out if he has enough speed to lift off without getting shot or falling off the cliff. And here is the kicker: your summer crush, that Swedish au pair you love so much, had to go back home and the only way to stay in touch with her is to call her under the watchful eyes of your father with his trusty chronograph. Remember, we are not in the WhatsApp age, yet. Just imagine it’s the mid seventies, you have one phone in the house, and it’s a rotary phone that you have to share with everyone - how did we ever survive? - and making a phone call is expensive, very expensive, especially long distance and in particular calling overseas. As such, it would make sense to be aware of the rate hike after the initial 180 seconds. It is, in fact, true that during the mid-century telephone rates would change and increase in three-minute intervals. One explanation that had been swirling around the Internet and one of the most plausible theories, was that the three-minute increments of the 30-minute chrono sub-dial were there to time international calls or pay phone calls. Let’s take a closer look and go back in time to find out what’s behind this mystery, specifically to the pre-digital age, a time before cell phones, Netflix, and self-driving cars. However, in our world of endless homage releases and vintage-inspired timepieces, one will find numerous examples of these in the wild, such as the Blancpain Air Command and the Longines Avigation Big Eye, among others.

Most modern chronographs have conventional 30-minute counters, highlighting each five-minute mark with a bolder or elongated hashmark. Granted, not all chronographs have this odd distinction, so don’t feel bad if you’ve never noticed them before.

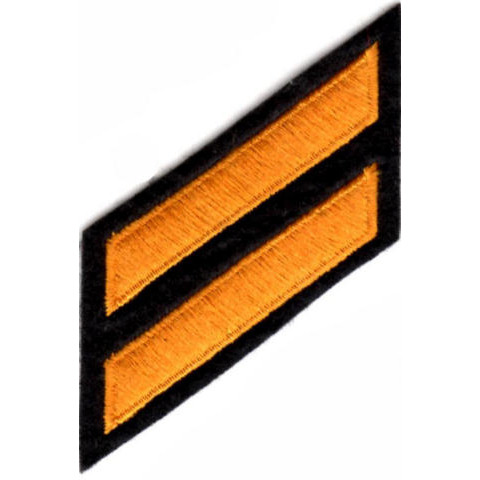

What do these strange lines mean who came up with them and why are they on your watch? You thought you did your research and knew everything there is to know about your precious timepiece, but you are stumped. You look down at your wrist with with pride, ready to conquer the world, when you notice these strange lines in the minute counter at the 3-, 6- and 9-minute marks.

Let’s say you’ve recently bought a brand new chronograph. I have two types of non-failure censoring - loss to follow up, and standard time on study censoring - and I would like to be able to show on the plot which censoring events are due to each type.This exploration of the case of the curious chronograph hash marks was contributed by Revolution Community member Achim Ruehlemann, whose first loves are watches, wine, vintage cars, tennis, skiing and his family. I have a question about color-coding the censoring hash marks in a Kaplan Meier curve, conditional on another variable. Notice: On April 23, 2014, Statalist moved from an email list to a forum, based at.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)